Premise

Being the *nix fanboy that I am, I love having terminal access to my system. Most *nix based OS’s have the same base set of awesome command-line tools. The majority of these are simply “set and run” programs, but some have Text User Interfaces, (TUI), as well. A few of my favourites include screen, bmon, htop and lynx. Be sure to check those out if you haven’t already.

If you’ve ever written a small command-line program that relied on any kind of user input, you’ve probably already coded your own rudimentary menu system at some point. It’s really not that difficult, but.. things can quickly get messy and you’d soon wish you had found an easier way of handling terminal control. Enter ncurses (new curses), a library for writing terminal-independent TUIs.

The project

There’s quite a few run-of-the-mill tutorials for curses out there, but doing a traditional “Hello World!” program just feels so uninspired. Instead we are going to do a simplified version of the classic game Snake, let’s call it PieceOfCakeSnake. In PieceOfCakeSnake you win simply by playing, there is no opponents, no consumables and no way of dying. Just a single, fixed-size, snake moving around in it’s little box world. The game starts right away upon launch and Snakey, our main character, is moving happily along from the get-go. The game ends when ‘x‘ is pressed.

Hammer and chisel

For no particular reason, I’m going to use Xcode for PieceOfCakeSnake and write it in C. If you want to use another editor be my guest, it’s much the same since it’s going to be run in a regular terminal anyway.

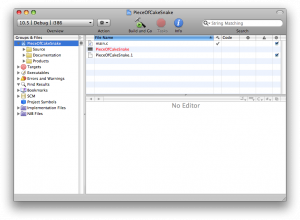

Now fire up Xcode and create a new project. Chose “Command Line Utility” > “Standard Tool”. Name the project and save it where you want.

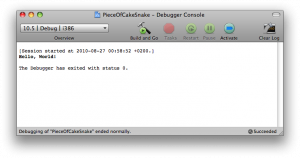

Xcode have already created a main.c file for us that simply outputs “Hello World!” and exits. Click “Run” > “Console” and click “Build and Go”. If all is well, the program builds without error and you should see something like this:

Now, ncurses comes native with Mac OS X, but for other systems you might need to install it beforehand. E.g. for Ubuntu there is the libncurses5 package.

There is still a little more to be done before we start coding. To get access to all the ncurses functions we have to tell the linker, to include the library at compile time. This is done by adding the line #include <ncurses.h> at the top of main.c and by supplying the linker flag -lncurses to the compiler. If you are compiling this from the terminal with GCC, the command would be:

gcc main.c -lncurses -o pocs main.c

Where pocs is the resultant executable. In Xcode however, we rely on the provided build system and so, the linker flag is set in the project properties. Click “Project” > “Edit Project Settings”, chose the “Build” tab and find the field named “Other Linker Flags” and insert “-lncurses”.

That should do it, we are set to go.

Let’s see some code

In this first step, we’ll create a world for Snakey, a square box positioned in the middle of the terminal screen. Here’s the code:

#include #define WORLD_WIDTH 50 #define WORLD_HEIGHT 20 int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { WINDOW *snakeys_world; int offsetx, offsety; initscr(); refresh(); offsetx = (COLS - WORLD_WIDTH) / 2; offsety = (LINES - WORLD_HEIGHT) / 2; snakeys_world = newwin(WORLD_HEIGHT, WORLD_WIDTH, offsety, offsetx); box(snakeys_world, 0 , 0); wrefresh(snakeys_world); getch(); delwin(snakeys_world); endwin(); return 0; } |

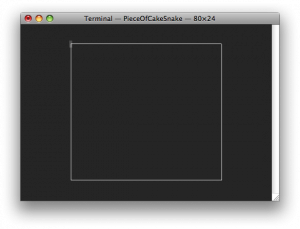

Running this example, you should see something like this:

Notice the WINDOW type. With ncurses everything is drawn on windows. By default, ncurses sets up a root window, stdscr, which backdrops the current terminal display.

To use it we call initscr(), which prepares the terminal for curses mode, allocates memory for stdscr and so forth.

The windows in ncurses are buffered, in the sense that you can do multiple drawing operations on a window, before making them show up on screen. To display the contents of a window in the actual terminal, the window needs to be refreshed.

For stdscr, this is done by calling refresh(), for child windows we use wrefresh(). This also shows the easy-to-remember naming convention used in the ncurses library – most functions that can be applied to stdscr, also has a counterpart, which applies to child windows, simply named by prepending a ‘w’ to the function name. E.g. refresh() and wrefresh(). We’ll se more of this in the finished version.

Instead of drawing the box manually, we take a shortcut by creating a new window and using the function box() to draw a border around the window. box() can use any displayable character to draw the borders. Using 0 defaults to a system specific line character.

Note: COLS and LINES are environment variables, that holds the current width and height of your terminal. That is the number of horizontal and vertical character positions available in the window.

The getch() function is simply there to pause program execution until some keyboard input is received. Thus a key press exits the program.

Functions delwin() and endwin() handles memory deallocation and returns the terminal to it’s former state. If these are omitted, the terminal will not behave as expected upon program termination and will probably need to be reset.

Time for some action

Now for the fun part – putting Snakey in his box and getting him to move about. Since this entry is about ncurses, I’m not going to go into the mechanics of the game itself. It’s a very simple implementation and the code should be rather self explanatory. You can download the source file here or just read from the following:

#include <ncurses.h> #define TICKRATE 100 #define WORLD_WIDTH 50 #define WORLD_HEIGHT 20 #define SNAKEY_LENGTH 40 enum direction { UP, DOWN, RIGHT, LEFT }; typedef struct spart { int x; int y; } snakeypart; int move_snakey(WINDOW *win, int direction, snakeypart snakey[]); int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { WINDOW *snakeys_world; int offsetx, offsety, i, ch; initscr(); noecho(); cbreak(); timeout(TICKRATE); keypad(stdscr, TRUE); printw("PieceOfCakeSnake v. 1.0 - Press x to quit..."); refresh(); offsetx = (COLS - WORLD_WIDTH) / 2; offsety = (LINES - WORLD_HEIGHT) / 2; snakeys_world = newwin(WORLD_HEIGHT, WORLD_WIDTH, offsety, offsetx); snakeypart snakey[SNAKEY_LENGTH]; int sbegx = (WORLD_WIDTH - SNAKEY_LENGTH) / 2; int sbegy = (WORLD_HEIGHT - 1) / 2; for (i = 0; i < SNAKEY_LENGTH; i++) { snakey[i].x = sbegx + i; snakey[i].y = sbegy; } int cur_dir = RIGHT; while ((ch = getch()) != 'x') { move_snakey(snakeys_world, cur_dir, snakey); if(ch != ERR) { switch(ch) { case KEY_UP: cur_dir = UP; break; case KEY_DOWN: cur_dir = DOWN; break; case KEY_RIGHT: cur_dir = RIGHT; break; case KEY_LEFT: cur_dir = LEFT; break; default: break; } } } delwin(snakeys_world); endwin(); return 0; } int move_snakey(WINDOW *win, int direction, snakeypart snakey[]) { wclear(win); for (int i = 0; i < SNAKEY_LENGTH - 1; i++) { snakey[i] = snakey[i + 1]; mvwaddch(win, snakey[i].y, snakey[i].x, '#'); } int x = snakey[SNAKEY_LENGTH - 1].x; int y = snakey[SNAKEY_LENGTH - 1].y; switch (direction) { case UP: y - 1 == 0 ? y = WORLD_HEIGHT - 2 : y--; break; case DOWN: y + 1 == WORLD_HEIGHT - 1 ? y = 1 : y++; break; case RIGHT: x + 1 == WORLD_WIDTH - 1 ? x = 1 : x++; break; case LEFT: x - 1 == 0 ? x = WORLD_WIDTH - 2 : x--; break; default: break; } snakey[SNAKEY_LENGTH - 1].x = x; snakey[SNAKEY_LENGTH - 1].y = y; mvwaddch(win, y, x, '#'); box(win, 0 , 0); wrefresh(win); return 0; } |

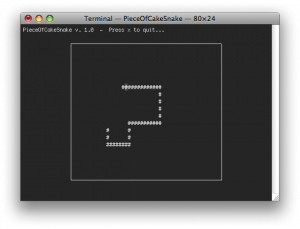

And here is what the game should look like in the terminal:

There is a few new ncurses functions being used here. Let’s start at the top. In main I’ve added:

noecho(); cbreak(); timeout(TICKRATE); keypad(stdscr, TRUE); printw("PieceOfCakeSnake v. 1.0 - Press x to quit..."); |

From top to bottom. noecho() subverts the terminal from printing back the users key presses. This is useful, since otherwise we would quickly have a lot of garbage on-screen from using the arrow keys to guide Snakey.

cbreak() disables line buffering and feeds input directly to the program. If this wasn’t called, character input would be delayed until a newline was entered. Since we would like immediate response from Snakey, this is needed.

timeout() sets an input delay, in milliseconds, for stdscr, which is applied during input with getch() and sibling functions. If the user doesn’t input anything within this given time period, getch() returns with value ERR. Useful in this part of the code, where we would like Snakey to move, even when we are not pressing any keys.:

while ((ch = getch()) != 'x') { move_snakey(snakeys_world, cur_dir, snakey); if(ch != ERR) { ... } } |

The keypad() function enables or disables special input characters for a given window. F keys and arrow keys for example.

printw() works like the standard library function printf. That is print a given string at the current cursor location.

To separate things a little, we have an auxiliary function move_snakey(), which handles movement and redrawing of Snakey within the box. There is a few ncurses specific functions in there as well:

You could chose to add and remove individual characters if you want to be explicit, but I’m lazy, so I clear the whole window and redraw it again every time Snakey has moved. Clearing is done with clear() for stdscr and wclear() for child windows.

The last function to mention is mvwaddch(), which moves, notice mv, to coordinate x, y, in a child window, notice w, and adds a character at that position.

The mv prepend, like w, is also a part of the naming convention of ncurses. Thus most drawing operations have an extended version, that besides the item to be drawn, takes a set of coordinates of where to move the cursor before drawing it. E.g. printw() and mvprintw.

Goodbye Snakey

PieceOfCakeSnake is a very simple demonstration and only shows a very small subset of the features available with ncurses. For the inspired reader however, it should be no problem extending the game with a menu system, a scoreboard and more, using only the small part demonstrated here.